In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman explained that we all pretty much live in bubbles of our own making. We each have a limited view of the world AND we for the most part assume that other people see the same things in the world that we do. He called this phenomenon WISIATI: “What I see is all there is.”

Actually, though, since we each have a unique set of experiences and beliefs, we often see totally different things in the world and interpret those things in totally different ways. The overlapping regions of our perspectives (spotlights) on the world are actually quite small.

Kahneman didn’t think there was much we could do about this fundamental aspect of human perception and awareness, and he saw it as one of the main causes of many of our disagreements and conflict.

Still, while our perspectives are limited, there is an age-old way to expand those perspectives. It’s called dialog. We can learn to acknowledge our limited perspective on the world and we can also learn to give others the benefit of the doubt when they say or do things that seem misguided or even malignant. Curiosity, empathy, humility and transparency can help.

Most people don’t go through their lives looking for ways to hurt other people. In many cases, they’re too busy working on their own problems to even notice what others are going through.

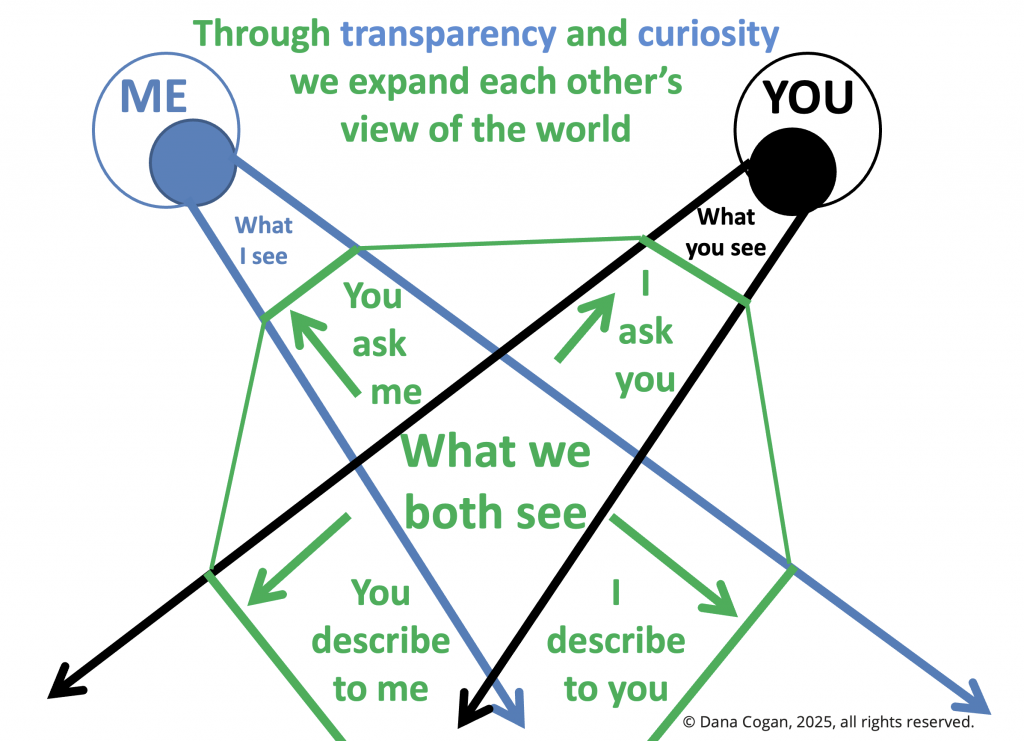

Many years ago, I developed this graphic to help my clients visualize what happens when we commit to the discipline of dialog. Some of my clients have found variations of this graphic useful. I use it as a reminder that our perspectives (yours, mine and everyone else’s) are naturally quite narrow and overlap much less than we might assume.

It also helps me remember that with a little effort we can expand each other’s field of vision so that we can see more of each other’ worlds, including a bit of each other’s hearts and minds.

Once I have remembered that no one else sees the world in exactly the same way as I do, it is much easier for me to give them the benefit of the doubt, and I start to feel a little more curious about what things might look like from my counterpart’s perspective. Looking at this graphic helps me remember and “feel” the importance of assuming that the people around me do what they do with positive intent or at least benign indifference toward me.

When I introduce this as a F/C reveal or to guide a facilitated dialog, we build it out it in steps, coloring in and/or adding text to show how the “shared” field of vision expands with each step. This might look something like:

1. Describe what I see now

2. Ask what you see now

3. Describe what I feel now

4. Ask what you feel now

5. Describe what I see as the ideal future outcome

6. Ask you what you see as the ideal outcome

etc.

I’ve also aligned the sections with some (obvious) question categories, etc. to make it easier for people to use this without a facilitator present.

It can be a surprisingly effective tool for getting people to

– notice the degree to which they haven’t taken the time to consider the gaps between their perceptions and those of their peers

– how easy it can be for us to help each other fill in the gaps

– how easy it is to agree on what needs to be done once the shared visual field has been expanded…

(By sharing this early version of this graphic, I have made it possible for anyone (who happens to be paying attention) to see that PPT design is definitely NOT one of my strong suits;) I have a prettier version that someone else made for me a few years ago, but this was the best I could do at the time when I tried to turn the flip chart into a slide.)

Curiosity and transparency don’t solve every problem we encounter in our efforts to get along with other and get something useful done in the world, but they do sometimes reveal realities and possibilities that we would otherwise miss through pure, simple and most importantly NORMAL and NATURAL ignorance stemming from the limitations of our perspectives.

—

ONE FINAL NOTE: There are of course situations in which you encounter someone who might in fact have negative intentions toward you or pose an imminent danger to you. I’m definitely NOT suggesting that dialog is what you need in those situations. Obviously, when you are in imminent danger, protecting yourself takes priority over dialog. For most – obviously not ALL – of us, though, these situations are rare. This is a judgment we each have to make on an ongoing basis based on circumstances.

© Dana Cogan, 2025, all rights reserved.